I’ve always had an interest in the history of exhibition curation, display/installation and design. This was written a few years ago and became a part of the PhD I was doing at the time. It’s part of a very brief interpretation of some early Twentieth Century exhibition installation and design. Looking back it’s far from complete though it was only a small part of a much bigger text. The Surrealists, Dadaists etc who were also pretty innovative in terms of installation design aren’t mentioned much in this instance. It’s also taken out of context as it was part of a bigger discussion on curation, archives and cultural regeneration etc. But I thought it might be interesting to share it as I rarely talk about the exhibition part of the Abridged concept (outside of a gallery environs) which inevitably has been shaped by what has gone before. Also display history is often forgotten in the curatorial and theoretical scrum that accompanies visual arts.

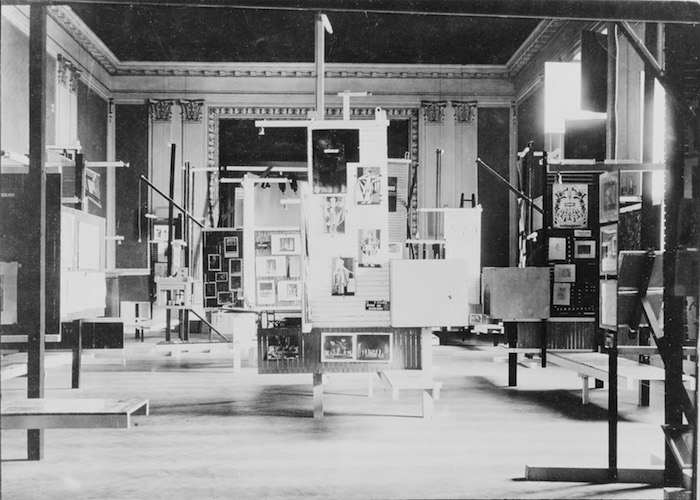

It is informative to note that exhibition design, in terms of installation, look and layout was being investigated in the first few decades of the twentieth century, especially in relation to improving the lot of the citizenry. As Staniszewski points out artists fascinated with the possibility of creating public exhibition spaces saw in installation design one of the many contemporary arenas of mass communication that could transform (or regenerate) modern life (Staniszewski, 1988, 4). For example Frederick Kiesler’s curation of the Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik (International Exhibition of New Theatre Technique) in the Konzerhaus in 1924 in Vienna (photo above) and again in 1926 at The International Threatre Exhibition in New York would develop installation techniques that would remove the artwork from its traditional home on the wall and bring it into the space of the spectator. Keisler, an Austrian architect, and member of De Stijl developed what he termed ‘Leger and Trager’ or ‘L and T’ method of display which he believed enabled the artwork to remove itself from the rather suffocating constraints of exhibition conventions.

The ‘L and T’ were essentially freestanding structures with vertical and horizontal beams supporting panels on which the work (in the Vienna show unframed drawings, photographs, designs and models of avant-garde theatre production) was mounted. Through a cantilever system these structures had cantilevers which allowed the viewer to adjust the works to the most comfortable viewing height. As the artworks were now physically apart from the actual structure (i.e. walls) of the building they were displayed in, an alternative to the traditional ‘salon’ style of overwhelming the wall space with tiers of paintings was developed. As Staniszewski comments:

with the L and T system, Kiesler devised a new physical framework for exhibition, he created a new ideological scaffolding for it as well…that set up a framework for viewing art that acknowledged its reception by a viewer as necessary for the creation of meaning (Staniszewski, 1988, p. 8)

The installation that Kiesler developed was informed by movements such as De Stijl, and Suprematist and Constructivist concepts that challenged the fixed viewpoint of classical perspective and can be read as a radical departure from traditional exhibition technique. Keisler would emphasise the interconnectedness of viewer and object in his exhibition design and particularly in his ‘Endless Theatre’ concepts which re-thought the boundaries between performers and audience. Kiesler theorized his ideas under the concept of ‘Correalism’ in which the art object (or performer) and importantly its environment are no longer isolated entities but should be considered of equal regard and are seen as completely interconnected and dependent on each other. Kiesler also articulated the interconnectedness in his book, Contemporary Art Applied to Window Dressing, which was published in 1929 and his ideas put into practice at Saks Fifth Avenue store in New York.

Thus we can see a determination to involve the spectator or in other words integrate the social into the art experience. In exhibition making, whether curation or installation [though both are best when not considered as separate entities] there is for the displayed object (and this goes for the whole show) the power to resonate:

to reach out beyond its formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex dynamic cultural forces, from which it has emerged and for which it may be taken by the viewer to stand … [where] the viewer is pulled away from the celebration of isolated objects towards a series of implied, often half visible, relationships and questions (Traue, 2000, p. 64).

This immersion of space, viewer and viewed was integral to another exhibition space – ‘Abstract Cabinet’ – designed by El Lissitzky to display constructivist or abstract paintings in the Spengel Museum Hanover, Germany in 1927 and curated by Alexander Dorner. Kantor describes it thus:

the gallery was a cubic space designed as a visual unity, incorporating the floor and ceiling as well as the walls – a total environment that enabled the viewer to participate in the activity of the displayed works (Kantor, 2002, p. 181).

The ‘Abstract Cabinet’ was both a gallery space and an installation, housed as it was inside another gallery. It was a version of Raum für konstruktive Kunst which Lissitsky had installed in Dresden in 1926. The gallery space was part of an overall redesign by Dorner of what had been a traditional nineteenth century museum, abandoning the display of work by schools and making the viewing experience an interactive activity with ‘atmosphere rooms’ intended to evoke the period of the work shown.