There’s a Peanuts cartoon that basically boils down to ‘Everyone has a best day ever’ – ‘What if you’ve already had yours?’ We kind of know that Charlie Brown, though only a kid and only on this planet a few years, has his best day already behind him. So what does he do? He makes do and tries to be as decent as he can. This of course is very hard to do in the cold world that at best tolerates him and at worse actively despises him. Remember in the FIRST EVER Peanuts from October 1950 has the line Good ‘Ol Charlie Brown…How I hate him! It’s not a good start…

Decency is defined as ‘behaviour that conforms to accepted standards of morality or respectability’ but that doesn’t really cover it. If the accepted standards of morality states (explicitly or implicitly) that one race is better than another or that one time of sexuality or gender should be promoted to the detriment of others then conforming to that isn’t decency.

Weirdly journalists thought of Peanuts as (for good or bad) aloof from the moral, societal and political controversies of the day:

“A number of commentators, however, accused Peanuts of being too aloof from the most serious national and global events of its time. Social ethics professor Roger Shinn of Union Theological Seminary faulted Peanuts for being too “detached” from real-world problems. The Boston Post asserted that “in the midst of wars, rumors of wars, clamor and controversy,” Peanuts was an “escape hatch into a ‘make believe’ world of serenity and laughter.” Even at the end of the strip’s fifty-year run in national syndication, as Americans mourned Schulz’s retirement announcement and attempted to interpret his legacy, journalists still viewed Peanuts as largely apolitical. “Inflation… and other current events,” wrote Newsweek’s Mary Voboril in late 1999, “seldom invade the gentle provinces of the strip.” In her reading of the series, the most pressing issues in postwar American politics were missing from the period’s most-read newspaper comic strip. “Hippies, Vietnam, Watergate, Iran-Contra, CIA spy scandals, impeachments, elections,” she listed to prove her point, “never found a topical home here.” [1]

To be fair, Schulz had a tendency, often to interviewers and reporters to sometime emphasise that he didn’t want to upset anyone or be controversial with Peanuts. Perhaps he didn’t feel the need to explain his work in great detail or he genuinely didn’t want to argue in public. This approach facilitated the analysis of Peanuts by sections of American society to fit into particular perspectives. For example the Religious (and often fundamentalist) Right took Peanuts to their heart after A Charlie Brown Christmas premiered on television. On the opposite end of the spectrum Peanuts was very highly regarded by students and counter-culture philosophers:

“To the countercultural mind,” Jonathan Franzen wrote, “the strip’s square panels were the only square thing about it. A begoggled beagle piloting a doghouse and getting shot down by the Red Baron had the same antic valence as Yossarian paddling a dinghy to Sweden. Wouldn’t the country be better off listening to Linus Van Pelt than to Robert McNamara? This was the era of flower children, not flower adults.” [2]

Though there has been of course great art that is one dimensional in its ‘message’ (for want of a better expression) the best has room for multiple readings. And let’s face it, people will read art how they want. Just ask Springsteen about how ‘Born in the USA’ has been articulated as a jingoistic/patriotic hymn. Peanuts though in Lucy having one of the loudest and (often) ignorantly opinionated kids in literature was subtle hence the difficulty in pinning it down to one continual particular concept or position.

Schulz was very critical of religion as patriotism which was beginning to take hold in the mid-century US and is now (thanks to the extreme Right’s courting of the Evangelical vote) prevalent. In 1967 he stated in a press interview how frightening it was that people were beginning to believe than Christianity and Americanism were the same thing. We can only imagine what Schulz would’ve thought of Trump’s popularity with the Evangelicals in contemporary times. The US has always had trouble with the concept of defeat. It goes against the American ‘dream’, a mythos that lasts or at least is propagated to this day. Officially America doesn’t lose, be it in Vietnam or Afghanistan even if unofficially the opposite is admitted:

Thinking about defeat is not merely taboo in U.S. strategic culture. It is illegal in some cases. In August 1958, Sen. Richard Russell expressed outrage that he had heard on the radio “that some person or persons holding office in the Department of Defense have entered into contracts with various institutions to conduct studies to determine when and how, and in what circumstances, the United States would surrender to its enemies in the event of war.” Russell proposed an amendment to the supplemental appropriations bill then under consideration that “no part of the funds appropriated in this or any other act shall be used to pay” for studies of this kind. While the Eisenhower administration (which protested that Russell misrepresented the studies he was condemning) and some senators pushed back against the amendment, it ultimately passed with 88 votes for and only two against.

That merely hinting at the possibility that U.S. surrender might be possible elicited a law prohibiting any federal funding of research on the topic exemplifies the American allergy to thinking seriously about defeat. In an era when it appeared that a major war would end in a mutual annihilation rather than surrender, this tendency was perhaps excusable. But, in the present, when near-peer adversaries are increasingly capable of defeating U.S. conventional forces on a theatre level, U.S. decision-makers can no longer afford to pretend that defeat is not a real possibility. [3]

Peanuts on the other hand as Schulz admitted was a study in defeat. There are no winners in the Peanuts world. The characters exist in a bleak continuum of existential angst and unrequited love. It’s the very opposite of the American Dream. The Peanuts kids are for the most part working/middle-class. Charlie Brown’s Father has his own barber shop, just as Schulz’s father does, though he’s still working class or at best lower middle-class perhaps. The narcoleptic Peppermint Patty, coming from a single parent family is also very unusual in cartoon strips of the time. We never see their parents, even though we know what those parents were doing at some point, with the addition of the most famous babies, Lucy, Linus, Schroder, Sally and Rerun. None of them are going to get wealthy we know though.

Most of the kids in the Peanuts world are also white. The ‘American Dream’ (however it is defined) was and indeed probably is still considered by many to be for white people only. It took a letter from Harriet Glick, a teacher from California to see the Peanuts world change:

Ms. Glickman recognized that loyal “Peanuts” readers might be nonplused, or even annoyed, by a new character. So she wrote a letter to Mr. Schulz in April 1968, shortly after Dr. King’s assassination, that made a reasonable case for adding a black character while acknowledging the risks involved.

“I’m sure one doesn’t make radical changes in so important an institution without a lot of shock waves from syndicates, clients, etc.,” she wrote. “You have, however, a stature and reputation which can withstand a great deal.” [4]

Schulz replied saying that whilst he and many other cartoonists would like to do just this but: but each of us is afraid that it would look like we were patronizing our Negro friends.

It was a well-intentioned if somewhat wishy-washy reply from Sparky and Harriet Glickman was not deterred suggesting that she talk to African-American friends about the introduction of a black character into Peanuts:

One of those friends, Kenneth Kelly, a neighbor with whom Ms. Glickman protested housing discrimination, wrote that adding a black character, without great fanfare and “in a casual day-to-day scene,” would allow black children to see themselves in popular culture and “suggest racial amity.”

Mr. Schulz responded to Ms. Glickman at the beginning of July that she should look out for a strip to be published toward the end of the month. [5]

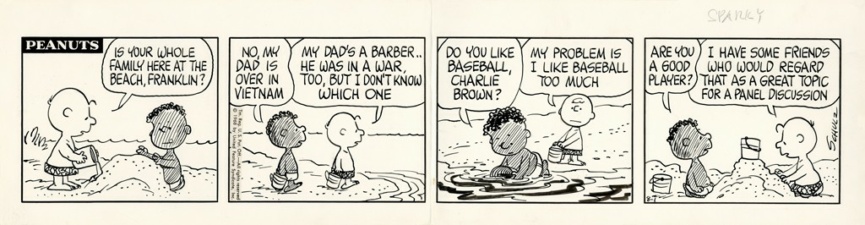

On July 31st 1968, Franklin, the first black Peanuts character appeared in a beach scene in which he returns a beach ball to Charlie Brown. We find out in the next day’s strip that Franklin’s father is in the army and away in Vietnam. This was very clever by Schulz who no doubt anticipated the opposition to the introduction of Franklin by pointing out that people were fine sending black people to fight in Vietnam but don’t want them in a cartoon strip. Schulz threatened any newspaper editors with withdrawing the cartoon from their paper if they objected to Franklin and such was the popularity of Peanuts at the time it was something he could have certainly done.

Franklin would appear regularly though there was frustration in some that he didn’t have any defining characteristic like the rest of the main Peanuts characters did. There is some justification in this frustration though perhaps Schulz was attempting to avoid clichés that for example Hollywood regularly fell and still falls into: the stereotypical black characters in early/mid Twentieth Century films. In early film history if we saw black characters at all they were usually in service or slaves. Contemporary Hollywood and television still has a tendency to incorrect representation. For example in 2016 black actors played 64 per cent of gang-member roles in Hollywood whilst in real life only accounting for 35 per cent of gang membership. The fact that Franklin was so ordinary was in itself very challenging. It told white American that this little black kid is no different with you. It also told them that they couldn’t pin him down as something or in other words marginalise him as easily.

This ‘normality’ was of course in staid white American society something to be sought after, particularly in the 1950s. Schulz got very bored with the original ‘normal’ Peanuts characters. They faded for the most part into obscurity throughout the decades. Shermy for example (named after a childhood friend of Schulz) was the ‘ordinary’ little boy that particularly in the 1960s was ill at ease with a rapidly changing society. Shermy (though we didn’t know his name) was the first Peanuts character to speak, and the first to attack Charlie Brown. ‘Normality’ is of course usually defined by those in power and the majority of society and it often protects its privileges. Hence the contemporary war on ‘woke’. As has been pointed out: what is labelled “woke” is often whatever social movement a particular country’s establishment fears the most. This turns out to be an ideal way of discrediting those movements. [6]

The USA in particular, especially since the rise of Trumpism has been caught in the midst of a ‘culture war’ that has as its target the ‘other’ and has at its source the recreation of a mythical America (possibly looking like the 1950s) that never existed:

The term ‘culture war’ was introduced to modern political analysis by the American academic James Davidson Hunter in his 1991 book ‘Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America’. Much of what we think about the term comes from the US, too, leading us to associate it with evangelical Christians, the Deep South, American-style racism and Wild West gun fanaticism. [7]

The Culture Wars are of course a fabrication against perceived slights, usually against white conservative, heterosexual people. Those that champion the battle against wokeness align themselves with the white working class whilst actively supporting policies that often harm that particular constituency (a contentious term as the white working class aren’t one community) and indeed the working class in general. In a recent poll in the UK, 76 per cent of people didn’t know what the culture wars were. When I say they are a fabrication, they are of course very real. As has been apparent (and explored by Abridged in many issues) reality and real are no longer the same, if they ever were. The Culture Wars are a real attempt to protect the privileges and structures of a particular class and race in the fame of changing societal attitudes using the media as a vehicle to convince a portion of the working class and dispossessed that their culture and heritage are under threat. Hence the focus on statues and history particularly in Britain and the US. Raising questions as to the nature of Empire and colonialism (particularly in schools and universities) is now considered a slight on ‘the country’ and almost treasonous. The idea of this is to be seen to preserve the status quo even when of course in the real world there is no such thing as an immobile status quo. The Culture Wars will end of course when it’s apparent that society has changed too much and another ‘war’ over something else will start when those in power feel threatened.

So how would have Schulz responded to the first two decades of the twenty-first century had he lived? We would probably have seen Lucy getting (more) angry as see checks her Facebook account and no doubt Charlie Brown would have agonised over his lack of social media followers and ‘likes’. Lucy is perhaps the Peanuts character that would have adapted to our contemporary completely connected technologically but perhaps emotionally distanced world. We can imaging her picking arguments with friends and strangers online. Her pursuit of Schroder would have reached new extremes with Instagram pictures and TikTok video of his playing whilst he looked disapprovingly on. Peanuts would’ve subtlety exploring contemporary issues as it always done. Whether that would have been enough for a contemporary audience is open to question in an often polarised world that has a tendency to weaponize. We can be sure the American Right would’ve grabbed Peanuts as their own. We can be sure Schulz would’ve disapproved. Then again, as newspapers have disappeared or lessoned in importance cartoon strips are not as prominent. Peanuts is probably known better for the cuteness of its merchandising and television programmes than it is for its actually strips. The Happiness Is…inspirational internet memes have washed over the bleakness of the strips, blinding us with positivity and well-being. There are new non-Schulz Peanuts comic strips/comics and some are entertaining. But it’s not the same. It’s probably impossible to be Schulz. I would have loved Sparky to continue to write Peanuts for years to come but what he did create echoes with us still so perhaps we’re not missing out his complex simplicity in our very complicated world.

Notes

[1] https://medium.com/history-uncut/youll-always-be-wishy-washy-charlie-brown-1ab54d9f649f

[2] Ibid

[3] https://warontherocks.com/2021/06/defeat-is-possible/

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/03/arts/harriet-glickman-dead-peanuts.html

[5] Ibid

[6] https://www.thenation.com/article/world/woke-europe-structural-racism/

[7] https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/culture-wars-the-british-right-is-picking-a-fight-it-wont-win/

Thanks to the Arts Council Of Northern Ireland for funding this essay