Adults rarely appear in the Peanuts cartoons. The Peanuts kids all struggle with adult existentialism and everyday stresses anyway, so there really isn’t any need for the depiction of grown-ups. One of the exceptions is the November 11th 1998 cartoon (below), in which we see two scruffy looking American infantrymen, ‘Willie and Joe’ looking askance at the new and very short recruit, who is of course Snoopy.

November 11th is Veterans’ Day in the US and Schulz often mentioned Mauldin in that date’s strips, no doubt to the puzzlement of many in the contemporary audiences, especially those beyond US shores. In another cartoon (below) Schulz gently chides his audience for this:

Mauldin in the 1940s was a very popular cartoonist on the US home front. In fact he won a Legion of Merit citation and a Pulitzer Prize and one of his cartoons even appeared on the cover of Time Magazine. There was also a best-selling compendium of his work. As the war ended he considered killing off Willie and Joe (which would’ve been a brilliant way to end it) to show that war kills even ‘the good guys’ but he was persuaded otherwise by his publishers. They’re final appearance would be in Schulz’s cartoon.

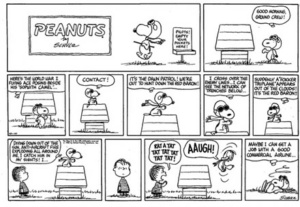

There was around two dozen ‘Mauldin’ cartoons. Snoopy, who’s mental landscape was often found to be in a WW1 dogfight (so to speak) with the Red Baron was the obvious choice to visit ‘Ol Bill’. The first (below) appeared on November 11, 1969. We see Snoopy putting on his uniform and probably heading to Bill Mauldin’s to drink root beer.

Schulz had a very personal experience of war. He had been drafted shortly after graduating from high school and spent three years in the military. Tragically, his mother died after one visit home which upset him for the rest of his life.. On February 19th 1945 Schulz’s Unit (the 20th Armoured Division) landed in France, made it’s way to Germany and eventually Austria. Along the way, they played a part in the liberation of Dachau concentration camp. Schulz himself was awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge for fighting in active ground combat under hostile fire.

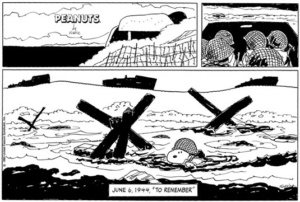

Although he arrived in France eight months after D-Day, the pivotal events in Normandy were featured in the Peanuts strip. In one of the most moving and strangest Peanuts cartoons ever published on June 06th 1993 we see in the first panel of a three panel strip, what appears to be bunkers and barbed war. The second we see faceless soldiers preparing on a boat preparing to rush ashore and the last and most powerful shows us a stunned looking Snoopy as an American G. I (general infantryman) crawling up to a Normandy beach. The only words are June 6, 1944, “To Remember”.

“Schulz got at least one reader’s attention. Dorothy Sand of Chicago wrote the Chicago Tribune on June 12, 1993, accusing them of having their “priorities mixed up.” Instead of carrying photographs of the Japanese royal wedding that summer, Sand thought that Schulz’s strip “should have been page one news.” (https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/06/06/how-snoopy-saved-d-day/)

At this point in time, Peanuts was part of the American landscape. A Charlie Brown Christmas had been an integral part of Christmas viewing for decades. The merchandising of Peanuts memorabilia made millions of dollars each years. And yet here we have Schulz going back to a day where thousands were slaughtered in order to defeat the Nazis. But there is no triumphalism in this cartoon, not even a hint of a future victory, just Snoopy crawling through muddy water and hoping he doesn’t get killed. You can imagine how appalled the marketing executives would be these days, advising against the darkening of the brand.

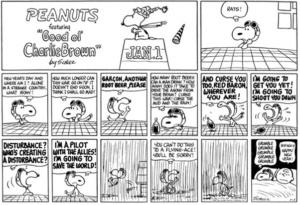

Schulz could have made an anti-war statement here but he didn’t. Indeed, occasionally in his Bill Mauldin cartoon’s there is an explicit though very subtle reference to the seemingly ever-presence of war. After WW2, the USA had got involved in Korea and of course the ill-fated ventures in Vietnam. During the 1980s there had been various skirmishes throughout the world and the invasion of Grenada occurred in 1983. Not to mention the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the various wars that tortured the Middle-East at the time. ‘Which War Was It, Bill?’ (below from a November 11th 1987) is a mixture of bathos and pathos to a very high degree.

The 1993 cartoon is not pro or anti-war. The cartoon is an appeal to remember. To remember the sacrifice of many but also to warn against the return of fascism. There is no nostalgia in the cartoon and nostalgia is a breeding ground for populists. Schulz talked about the loneliness of being in a war and we see Snoopy, not with his platoon but also and vulnerable. He will either make it to (comparative) safety or he will get shot dead. Peanuts was (though not by Schulz) and probably still is considered a children’s cartoon, but implicit in the cartoon is very adult political and social comment.

The next year would see Schulz really drive the point home in a series of week-long (Monday to Friday) daily strips albeit in a more humorous manner (below):

Schulz would have Snoopy imagining he’s part of the D-Day landings using the kids swimming pools and gardens as his Omaha Beach. The kids of course have no access to this imagined landscape so have no idea what he’s doing. This perhaps is another gentle comment on the lack of knowledge and understanding from contemporary generations. But again though Snoopy plays the “World Famous G. I” there isn’t any hint that war is easy. In the June 09th strip we see the “brave infantryman” throw grenades at an enemy fortification (Charlie Brown’s door) any hint that Snoopy is enjoying himself is undermined by the following day’s strip (below):

Here we see Schulz use the infamous lie that ‘It’ll be all over by Christmas’ phrase from WW1. This strip, the last in the series of D-Day cartoons for 1994 depicts Snoopy as a G.I who wants it over and wants to go home. The fact that Schulz uses a discredited first world war motif indicates that Snoopy is being misled or even lied to.

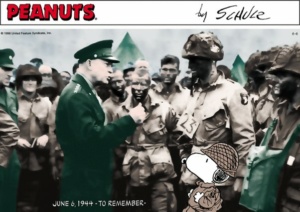

In 1996 and 97 Schulz would simplify the 1993 strip further and essentially repeat the final panel of the 1993 strip. 1998 would bring a radical departure for Schulz and the Peanuts D-Day strips. It was a colour photograph (below) to which Snoopy is added. We see him and other troops listening to General Eisenhower.

“Of all my D-Day cartoons, this Sunday page created the most interest from readers, who remarked that it was often the only reference to that momentous day of June 6, 1944, in their newspapers. Most gratifyingly, I heard from those in the picture and still with us, family members, and friends of the men talking with General Eisenhower.

The photograph itself was taken just before these men of the 101st Airborne Division parachuted into Normandy. According to Wallace, who was the youngest lieutenant with the number 23 on his chest, he had just been asked by Ike where he was from.

“Michigan, Sir.”

Ike brought up his thumb and said, “Go get ’em, Michigan.”

(https://archaeolibris.blogspot.com/2010/06/peanuts-and-d-day.html)

Of course, despite the bravado Eisenhower knew he was sending many of these troops to their death so it’s said that he actually talked to the men mainly about fly-fishing to keep their mind on other things. No doubt the men were perfectly aware of this. Towards the end of the 1990s Schulz was finding drawing the strip more difficult. Indeed his last strip would be on 13th February 200 so perhaps Schulz thought that this would be a different but still poignant manner of remembering D-Day. It was certainly very unusual.

*

We’ve been discussing World War 2 and Schulz/Snoopy’s response to it but we would be remiss not to discuss the war that provided the main arena for Schulz’s/Snoopy’s flights of fantasy. Snoopy had began life as a pretty ordinary dog. His first words, so to speak, in a March 1952 strip, were actually in the form of a thought balloon, came in response to Charlie Brown laughing at his large ears Snoopy feeling sorry for himself, wonders: “Why do I have to suffer such indignities!?”

As the years progressed he developed a remarkable and at time very strange inner-life. He often abandoned the children in favour of imaginative flights of fancy, the most consistent and definitely the weirdest was his ‘WW1 Flying Ace’ persona and his continuous losing (in the comic strips at least) battle with The Red Baron ( Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthhofen).

The Flying Ace persona (above) first appeared on 10th October 1965 in which Snoopy imagines his doghouse to be a Sopworth Camel. He would battle the Red Baron for decades to come until eventually Schulz got tired about jokes about war and instead the focus would be on lost love and loneliness, something of a Peanuts (and Schulz) speciality.

Not everyone was a Snoopy fan:

There was something fundamentally rotten about the new Snoopy, whose charm was based on his total lack of concern about what others thought of him. His confidence, his breezy sense that the world may be falling apart but one can still dance on, was worse than irritating. It was morally bankrupt. As the writer Daniel Mendelsohn put it in a piece in The New York Times Book Review, Snoopy “represents the part of ourselves—the smugness, the avidity, the pomposity, the rank egotism—most of us know we have but try to keep decently hidden away.” While Charlie Brown was made to be buffeted by other personalities and cared very much what others thought of him, Snoopy’s soul is all about self-invention—which can be seen as delusional self-love. This new Snoopy, his detractors felt, had no room for empathy.

(https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/11/the-exemplary-narcissism-of-snoopy/407827/)

It’s certainly true that Snoopy often disappearing into his own fantasies, especially the First World War fantasies. The children became characters in his fiction: Charlie Brown, Linus, prison guards. Marcie and Peppermint Patty cute French love interests or waitresses. Even his brother Spike (much to his bemusement) became a ‘blighter’ in the trenches. If Snoopy had been actually in a war this constant retreating into military fantasy could be seen as perhaps a signifier of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Maybe Schulz, though there isn’t any other evidence of it, it has to be said, was suffering a little PTSD that emerged as a dog pretending to be a fighter pilot (and a not very successful one at that) in one of the most vicious wars ever fought. Another indication of how broken Snoopy is that when most people retreat into fantasy they imagine themselves better than they are, richer, wiser, more athletic etc. Snoopy is a terrible pilot in the comic strips. Most people would imagine shooting down the Red Baron but the Baron is evidently a better pilot and Snoopy frequently ends up with a bullet riddled Sopworth Camel/Doghouse. Why would anyone imagine that. Unless perhaps Snoopy shares the same insecurities that plague the rest of Peanuts cast?

When he marches alone through the trenches of World War I, yes, of course, he is fantasizing, but he also can be seen as the bereft young Charles Schulz, shipped off to war only days after his mother died at the age of 50, saying to him: “Good-bye, Sparky. We’ll probably never see each other again.”

(Ibid)

The Vietnam War was also influencing and poisoning American society for quite a bit of the Peanuts run. It’s been argued that whilst Schulz was not open in his opposition to the war, there are definitely hints that he at least was on the side of the soldier in this seemingly futile war that America would not and could not win. In fact it has been suggested that the fact that Snoopy always loses to the Red Baron is a comment of the US’s inevitable defeat:

Snoopy’s alternative identity as a first world war flying ace — with his doghouse propeller plane — was a childhood favourite. It never occurred to me to read the strips as commentaries on the Vietnam war. Yet they were. It is telling that Snoopy never defeated his arch enemy, the Red Baron, and equally notable that the strips became more bleak as the war went on. “I’m exhausted,” Snoopy complains in 1971. “This stupid war is too much.” Readers got the message: Schulz supported the fighting man, not the war. The soldiers in Asia got the message, too.

https://www.ft.com/content/d3f469ab-d215-48e8-b83c-ea0537d08174

There are also numerous instances of the Peanuts kids usually very reluctantly, being ‘drafted’ to summer camp, with Sally in particular being generally appalled by what she is made to suffer. However we go back to Snoopy for a very gloomy start to 1967. We see him (below) thinking no doubt what many soldiers in Vietnam were thinking at the time. He’s alone in a strange country and getting angrier and more frustrated by the moment. He get’s chucked out of the bar/his (somehow) doghouse for causing a scene: You can’t do this to a Flying Ace! You’ll be sorry! He exclaims. Schulz was from his own experience knew that not only did the conscripts suffer during the war, they were often forgotten after the war, even though they were considered ‘heroes’.

As Darowski observes, the references to this ‘stupid war!’ weren’t lost on Schulz’s readership. He points out that the Flying Ace character was introduced during a time in which the Vietnam war seeming to be pointlessly dragging on and during 1967 and 1968 over seventy times (The Comics of Charles Schulz, The Good Grief of Modern Life, Joseph J. Darkowski, Snoopy’s Signs of the Times, P128). However as the war progressed and the death toll rose, Schulz was getting more uncomfortable with Snoopy fighting the Red Baron and so would tend to have his the Flying Ace being lonely or flirting with café waitresses.

During the 1960s, Peanuts was generally everywhere in American society. Millions of dollars were made from memorabilia so it was inevitable that characters from the strips would be used on both sides of the pro/anti war divide. In fact Schulz, being the somewhat contradictory gave permission for the characters to be used officially by the US military he was also well aware that both the soldiers used them more ironically and that the anti-war coalition also used them in protests.

In fact Schulz in as a subtle manner as ever would reference the divide between the youth and establishment in a series of strips in July 1970. Snoopy is invited to make a speech at the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm, where he was born and is mortified to be heckled, hit on the head with a well-aimed dinner dish and even tear-gassed in the ensuing trouble.

We later find out that the protest is about ‘War- Dogs’ Being sent to Vietnam and not coming home. Sometimes it’s the most understated of messages that are the most powerful. Though of course Schulz, perhaps emphasizing the indifference or obliviousness of our guest speaker, has Snoopy meet a girl beagle ‘with really soft paws’ amidst the rioting and smoke, become smitten and forgets. Of course being Peanuts where all love is futile and unrequited she is sold and he never sees her again.

Snoopy was the perfect conduit for Schulz to explore war, suffering and personal/societal remembrance. His inner imaginative landscape could be adapted to serve as a subtle critique of Vietnam or society’s failure (as Schulz saw it) to remember those lost there lives in WW2. Snoopy was essentially a blank template for Schulz to use. Charlie Brown imagining himself crawling up a Normandy beach or getting shot down by the Red Baron would have been at best a too, for Schulz, obvious ‘sending our kids to die in war’ message whilst at worst we would’ve focused on the boy himself. Sending the ultimate canine narcissist, who barely remembers the name of the boy he depends on for his food, water and shelter was much more powerful. A lost dog in a lost world. Schulz, like most of us didn’t like war but he had empathy for the young soldiers that fought and died in their thousands. He identified with the Willie and Joe characters created by Bill Mauldin more than he did with the generals. He used Snoopy to articulate the pain and loneliness of and need for remembrance in a powerful but subtle manner.

Violence, pain and fear was an integral part of the Peanuts world. Whether it was the early bullying of Charlie Brown by Patti and Violet to the physical and confrontational vocal violence of Lucy to her brother Linus in particular it was a constant presence. Even one of the last major characters, Rerun, suffered on the back of his mother’s bicycle, in constant terror of crashing. Then there was the violence of not meeting your potential, or of it being cut short. Not to mention the loneliness of unrequited love, a staple of the Peanuts world. Whether the quite cruel world of the Peanuts can be completely put down to Schulz’s personal experience in WW2 is debatable but there is no doubt that it influenced him and his strip significantly.

Thanks to The Arts Council of Northern Ireland for making this essay possible through support from their SIAP funding programme. It will also appear in the Honest Ulsterman.